The onset of ChatGPT and many other open-source LLMs have revolutionized the world and the way work happens in all sorts of industries. But very few of us know that

transformer-based models are the mother of all these magic tools- including BERT, GPT, and all the buzzwords around large language models.

I have struggled to understand the underlying concept and the working principle of Transformer, and I believe many struggle in the same way.I am going to publish a series of

articles on the Transformer to simplify the concept and break down things into small pieces. I believe this will help many to understand these complex concepts easily and

help them to break into this domain.

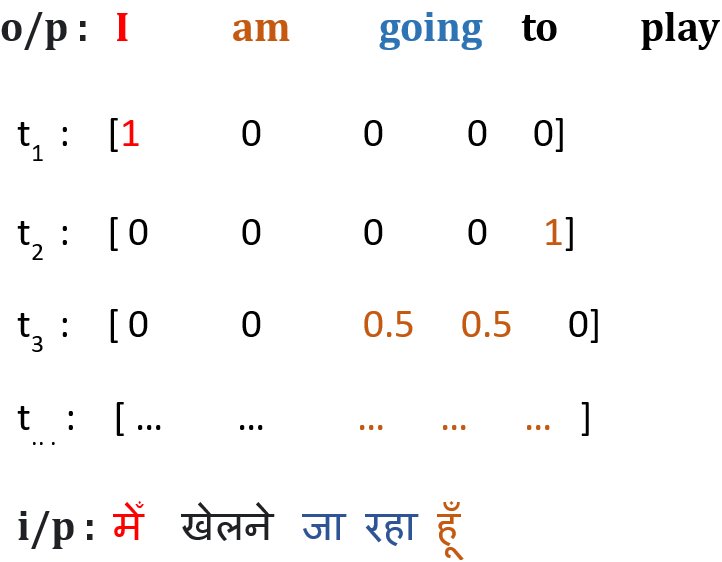

To understand the transformer architecture, first, we have to understand the attention mechanism- the main component of transformer architecture

and the concept of self-attention, and finally, the full Transformer Architecture. Maintaining the conceptual logic above, the following are the three articles that

I am going to publish. The first article in the series is “The Birth of Attention Mechanism”.The second article in the series is “Self-Attention”, and the third article is “Transformer”

We are going to understand the attention mechanism in the context of language translation using seq2seq (encoder-decoder) architecture.

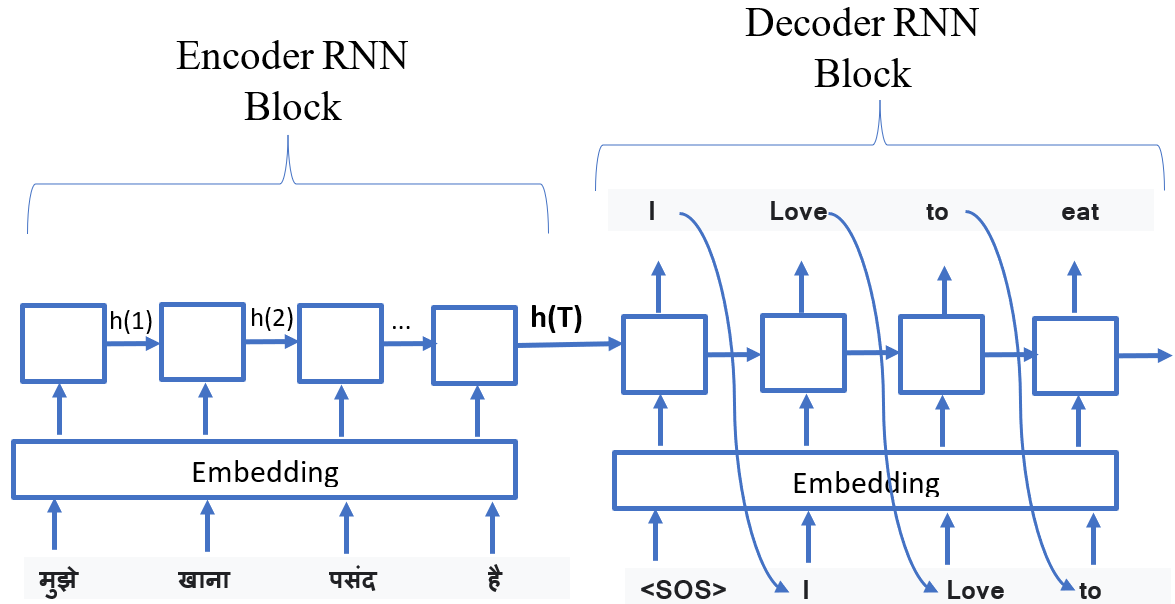

In the example given below in Fig.1, a Hindi sentence “मुझे खाना पसंद है” is fed into an encoder which has been translated(decoded) by

a decoder into English as “I love to eat”.

The encoder is used to ingest the input. It simply computes

all the h of T’s (i.e. h(1), h(2), …) at every time step of the input and gives one final hidden state vector,

which we'll call h(T), assuming that the input sequence has a length of T.

Here, h(T) is the output of the encoder, which is also the input to the decoder.

We can think of h(T) as a vector, which is a compressed representation of the input sequence.

Figure 1

Let’s see the decoder in detail.

Every RNN unit has two sources of input data, the first being the actual input and the second being the previous head state. The decoder is also an RNN but a different RNN from the encoder. In this diagram, the inputs go along the bottom of the RNN unit while the previous head state comes through the left. For a normal RNN, the initial hidden state is usually just a vector of zeros, or maybe some trainable but fixed vector. In this case, for the decoder, the initial hidden state actually comes from the output of the encoder, which is h(T). Thus, the job of the decoder is to decompress the compressed representation of the input.

What goes into the bottom of the decoder RNN unit?

At the beginning, there's a special token called <SOS> which indicates the start of a sentence or sequence.

The decoder RNN acts like a text generation tool, similar to how forecasts are made in time series analysis,

where it predicts the next element based on previous ones, such a model is also known as an autoregressive model

or causal model . So, starting with the <SOS> token and an initial hidden state, we predict the first word of

the translated sequence. After getting this first word, we put it back into the decoder as input, using it to

predict the second word in the sequence. We keep repeating this process until we've generated the entire translated

sequence. To know when to stop, we watch for the special end token produced by our model, signaling that the translation

is complete.

Note that, we need a lot of data sets containing paired Hindi sentences and equivalent English sentences

to train the model, and only after the model performs the translation as shown in the diagram above.

Problem with Seq2Seq

- Every input sequence is converted using an encoder RNN into a single vector. Here's the problem - What if the input sentence is very long? The final encoder state h(T) always has the same size and has to remember the whole input.

- Is this how we translate text as humans? No! More likely, we focus on a few words at a time.

To Solve this Problem: Attention is originated for Seq2Seq

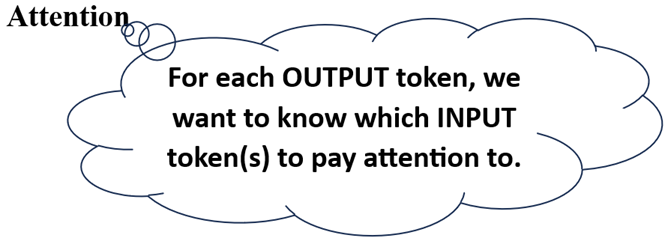

Let’s try to understand this attention concept with a simple example, where the input: “मेँ खेलने जा रहा हूँ “ is fed into

an encoder and translated into “I am going to play” as an output from the decoder as shown in fig.2 below.

In this figure ‘i/p’ at bottom represents input sequence and ‘o/p’ at top rerpesents output sequece.

Here, the list '\( t_1 \)'contains the values for attention that output at time step 1 should pay attention to all input

sequences . The list ' \( t_2 \)' contains the values for attention that output at time step 2 should pay attention to all

input sequences and similarly other lists are also representing attention values for input sequences for different

output at different time steps.

Figure 2

Let’s understand the attention values inside list 't1'. When we're aiming to generate the first word 'I' in our output,

what we're actually doing is figuring out the likelihood of each input word being the one we should focus on. At this stage,

it's fine if we don't know the translations for 'खेलने' or 'जा रहा' or 'हूँ', as long as we know the translation for 'मेँ' because that's

the word we need to generate first. So, we can simplify things by saying that, at this point, we only need to pay attention

to the first word in the input and can ignore everything else. This is the reason the attention value is 1

for the first input (मेँ) and 0 for all other input sequences.

What about the second time step word “am” in output? We just need to focus on the last word हूँ in the input,

and thus, the list ‘t2’ contains attention value 1 at last and 0 for all other input sequences.

What about the third time step word “going” in output? Is it always going to be that we only need to focus on one word at a time?

No. We will focus on two input sequences ‘जा ' and 'रहा’ and ignore everything else. This is the reason,

the list t3 contains attention values 0.5 and 0.5 at respective time

step positions of ‘जा ' and 'रहा’ and the remaining all are zero. Similarly, for the remaining time step.

Is this the encoder-decoder architecture doing, that we saw previously in Fig.1? No! Every time step

focuses on the encoding of the entire sentence (i.e. final h(T))

because that is the encoding that we are feeding to every time step. This is the problem we need to fix.

We need to learn to pay attention to certain important parts of the sentence. Ideally, at each time-step,

we should feed only the relevant information i.e. encodings of relevant words to the decoder.

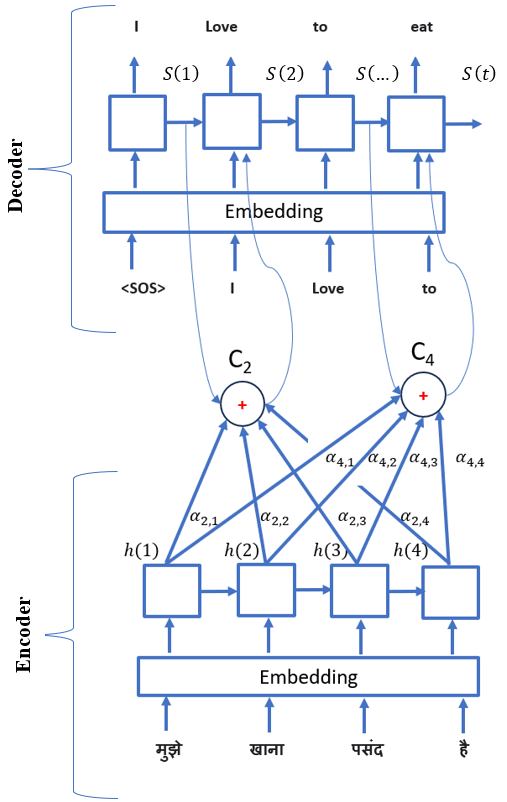

Improved Encoder-Decoder Architecture with Attention

Let’s see how to improve the previous encoder-decoder architecture with the concept of Attention.

In the given Fig.3 below, the decoder is drawn on top of the encoder and instead of feeding only

the last hidden state of the encoder to the decoder all hidden states are fed into the decoder at each time step

with some weightage noted by alpha. For the sake of simplicity, connection for only output at time state t=2 and t=4 have shown.

A weighted combination of each output is taken from the encoder cells (i.e., vector of the same shape) and fed

into each step cell of the decoder. Assume for the time being that, we got these alpha’s

(i.e. attention weights for each hidden state from the encoder) from some magic, we will figure out how to calculate it.

For output at the time state t=2 i.e. ‘Love’,

\(α_{2,1}\) : is the weight of attention that it should pay to input at time state 1

\(α_{2,2}\) : is the weight of attention that it should pay to input at time state 2

\(α_{2,3}\) : is the weight of attention that it should pay to input at time state 3

\(α_{2,4}\) : is the weight of attention that it should pay to input at time state 4

Similarly, for output at the time state t=4 i.e. ‘eat’,,

\(α_{4,1}\) : is the weight of attention that it should pay to input at time state 1

\(α_{4,2}\) : is the weight of attention that it should pay to input at time state 2

\(α_{4,3}\) : is the weight of attention that it should pay to input at time state 3

\(α_{4,4}\) : is the weight of attention that it should pay to input at time state 4

Figure 3

Context Vector

Now, defining weighted combination as a context vector, say for output at time step 4:

\( C(4) = α_{4,1} * h(1)+ α_{4,2} * h(2) + α_{4,3} * h(3)+ α_{4,4} * h(4) \)

Denoting:

Input time step by j=1, 2, ..., T

Output time step by i =1,2, ..., t

We can generalize the above equation as a Context vector: \( C(i)=\sum_{j=1}^{T_x} \alpha_{i,j}h(j) \)

Here, the context vector is simply the weighted sum of h’s where the weights are the alphas.

So, this is the basic idea behind attention. We have weights from every input to every output,

which tells us how much each output should pay attention to which input.

Calculating Attention Weights

Before calculating alphas, let’s introduce a term called alignment score noted by \( e_{i,j} \) and defined

as: at \( i^{th} \) time step of decoder, how important is the \( j^{th} \) word in the input.

This should depend on or should be a function of jth word and whatever has happened in the decoder so far.

Note, \(S_1, S_2…, S_t \) are decoder side hidden states.

We are interested in \( e_(i,j) \) for all the input words. For \( j^{th} \) input word, we are interested in knowing how important it is for the ith time-step output of the decoder. There are several ways this function can be defined and no need to know at this moment but the intuition that it depends on\( S_{i-1} \),and \( h_j \) is sufficient.

Now across all the input words, we want the sum of this score value to be one. We don’t want some arbitrary weights. It is just like probability distribution over what word is important by how much. We can achieve this by taking SoftMax of the score.

Attention Weight, \( α_{i,j} \) denotes the probability of focusing on the jth word to produce ith output word.